Lab-Grown Organs: Progress and Challenges

Lab‑grown organs—created in a laboratory rather than harvested from a donor—delivered on‑demand, size‑matched tissues could transform the mortality gap in organ failure. According to the American Society of Transplantation, roughly 83,000 patients in the United States await transplant, and organ shortages grow annually. The promise that stem‑cell‑derived tissues and 3D‑bioprinted constructs may supply organs without dependence on a donor chain is both an engineering triumph and a public‑health imperative.

Scientific Breakthroughs in Tissue Engineering

Early tissue scaffolding experiments in the 1990s laid the groundwork for what is now an exponentially growing field. The first FDA‑approved bioengineered kidney‑derived product, Cord Blood‑Derived Mesenchyme‑Stem-Cell‑Produced Bone Marrow (CureBone), exemplifies regulatory acceptance, albeit for a niche indication.

Key research milestones include:

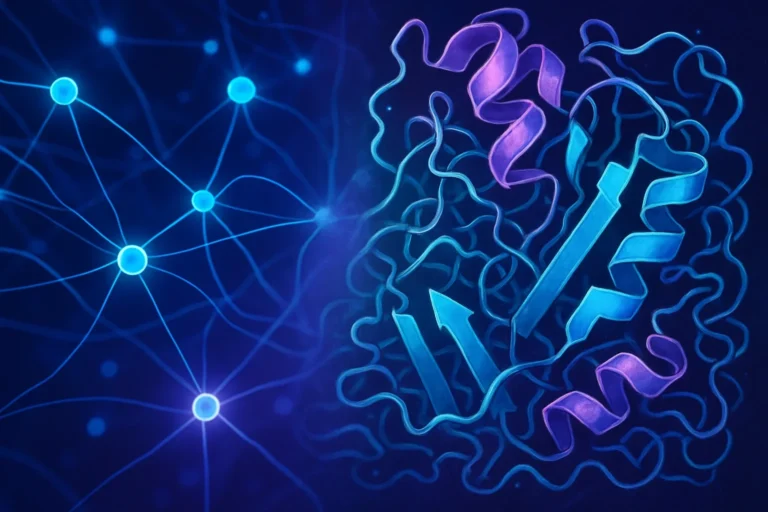

- Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) allowing patient‑specific cells that reduce rejection risks.

- Discovery of self‑assembling peptide hydrogels that mimic the extracellular matrix, enabling vascular network formation.

- Collaboration between Harvard School of Public Health and MIT producing perfusable 3‑D micro‑tissue constructs that show autoregulation of glucose and oxygen.

These breakthroughs underscore that the “bio‑print” is moving from a proof‑of‑concept to a scalable therapy.

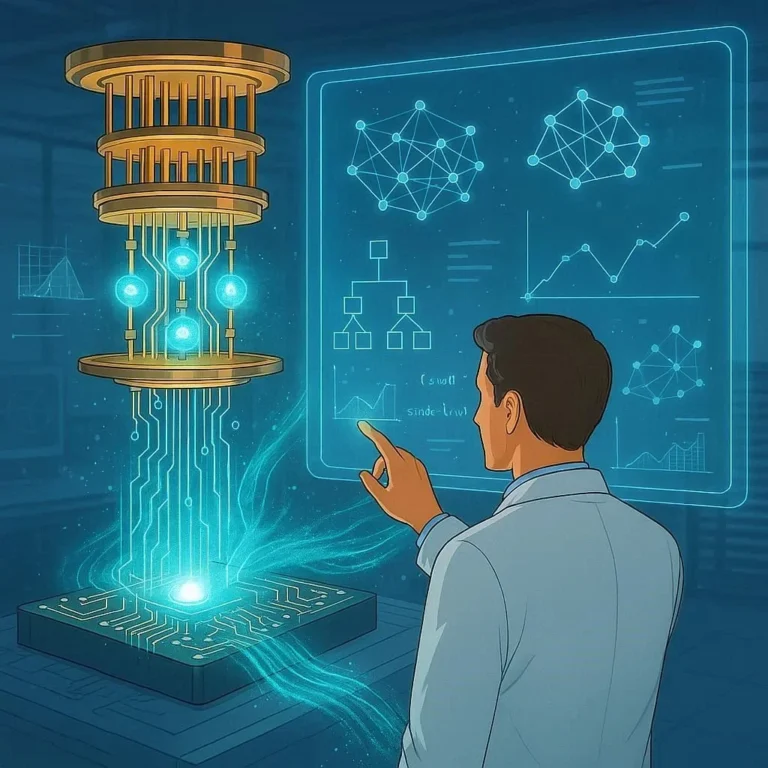

3D Bioprinting Technologies & Bioinks

3D bioprinting technology has matured beyond inkjet modalities to include extrusion, laser‑based systems, and bioprinting‑compatible micro‑fluidic bioreactors. The most widely adopted platforms now incorporate real‑time imaging and closed‑loop oxygen delivery to maintain cell viability during printing.

Bioink Innovations

- Alginate‑Gelatin Methacrylate (GelMA) hybrids provide shear‑thinning flow and crosslinking post‑printing.

- Decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) bioinks preserve native biochemical cues, improving endothelial cell alignment.

- Synthetic polymer composites (e.g., polyurethane‑based) offering adjustable mechanical stiffness for load‑bearing tissues such as heart valves.

These formulations have been successfully employed in pilot studies to create miniature heart valves that survived in vitro for 12 days while maintaining valve‑like flow dynamics. For deeper technical detail, check out the Wikipedia entry on 3‑D bioprinting.

Regulatory Pathways & Clinical Trials

Regulatory acceptance remains a dual‑edged sword: safety scrutiny is stringent, yet slow progress fuels investor frustration. The FDA’s Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy (RMAT) designation has granted expedited pathways for several skin and cartilage bioengineered products. Upcoming milestones:

- Phase I/II trials for a bio‑printed, perfusable liver lobule (Genome Cycling Institute’s project) are scheduled for 2025.

- The European Medicines Agency (EMA) is revisiting its guidance on “combination products” to accommodate layered organs that integrate cells, biomaterials, and devices.

These pathways illustrate a nascent framework poised for clinical translation once safety, reproducibility, and quality benchmarks are met.

Ethical, Social & Economic Implications

Lab‑grown organs bring us hyper‑personalized therapy, but also complex ethical questions:

- Equity of access: Initial costs will likely favor high‑income patients; public health frameworks must anticipate subsidies.

- Consent & traceability: Defining ownership of a patient‑derived cell line raises privacy concerns.

- Cultural attitudes toward engineered tissues: Religious and philosophical viewpoints may differ widely worldwide.

From an economic perspective, the projected global market for organ bioprinting is estimated at USD 13.3 billion by 2028 (source: MarketsandMarkets). Public‑private partnerships are essential to spread the upfront capital burden.

Current Market Landscape & Investment

Investment in regenerative technology has surpassed USD 4 billion over the past three years, with major biotech firms, venture capital funds, and even governments stepping in. Notable funds include:

- NIH’s Regenex Cord program awarding 4 $million to an organ‑on‑a‑chip consortium.

- GVG Capital’s $200 million round to a company developing a fully vascularized pancreas.

- The European Union Horizon 2020 grant of €30 million to a multi‑institution consortium focusing on brain organoids.

Despite the influx, commercial packaging remains limited to smaller, niche organs like trachea, cornea, and liver lobules, whereas whole‑organ integration such as kidneys lags behind.

Key Challenges and Limitations

- Vascularization depth: Beyond 200 µm, passive diffusion cannot sustain cell survival—advanced perfusion systems or micro‑cannulation are needed.

- Immune response: Even autologous cells can trigger inflammation; novel immunomodulatory coatings are under testing.

- Scale‑up reproducibility: Ensuring identical micro‑architecture across batches is a yarn for QC teams.

- Regulatory harmonization: Divergent international standards create logistical roadblocks for global clinical trials.

- Ethical sourcing of stem cells: Donor consent protocols must align with international guidelines (e.g., ISSCR).

Mitigating these hurdles requires cross‑disciplinary collaboration—materials chemists, cellular biologists, data scientists, and ethicists.

Future Trajectories & Research Opportunities

- Genome‑edited iPSCs to reduce immunogenicity while preserving organ functionality.

- Bioprinting with parametric control of shear forces to orient cells in anatomically correct geometries.

- Hybrid biofabrication—combining 3D printing with micro‑fluidic organ‑on‑a‑chip platforms for real‑time viability assessment.

- Artificial intelligence in bioink selection to predict print failures and optimize cross‑linking kinetics.

- Public‑private data sharing to accelerate standardization of quality metrics.

Collective research may culminate in the first bio‑printed, fully functional human kidney fitting into a standard 3‑D electron microscope. That would be a watershed moment for disability‑free longevity.

Conclusion & Call‑to‑Action

Lab‑grown organs stand at the intersection of hopeful science and real‑world necessity. The trajectory is clear: from bench‑side bioprinting to bedside delivery, each milestone addresses both promise and responsibility. Researchers and investors are called upon to pace technical innovation with robust ethical frameworks, while policymakers should draft forward‑looking regulations that encourage safe scaling.

Are you curious about how your stem cells could one day power the next generation of organs?